Blanche Knopf, who founded Knopf with her husband Alfred in 1915, considered translations of contemporary European literature central to her list. Both theories, however, are wrong.īy 1946, the war in Europe had been over for a year, enough time for English language publishers to begin thinking about what literature published in Nazi-occupied Europe was worth translating.

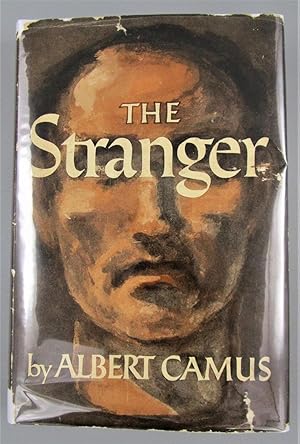

We could imagine, for example, that in the melting pot of New York, the immigrant publishing firm Knopf had a sense of foreignness that directed them towards The Stranger, whereas the English publisher Hamish Hamilton, in class conscious Britain, was more aware of social exclusion – hence The Outsider. So why has the novel always been called The Stranger in American editions, and The Outsider in British ones? The two titles tempt us to fill in the blank with cultural or political theories. An étranger can mean a foreign national, an alienated outsider or an unfamiliar traveller. It is hard to sum up a writer’s work in a new language, and once a title is on the cover, readers start to know the book by that name. Choosing a title is among the most important decisions a literary translator must make. The Outsider or The Stranger: the right title for the English language translation of Albert Camus’s 1942 classic, L’Étranger, isn’t obvious.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)